This story was produced with support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

A nickel refinery in Lawton, hoping to help solve America’s critical minerals crisis, has been the center of debate. After facing pushback from three local tribes, questions loom over the strength of Indigenous sovereignty.

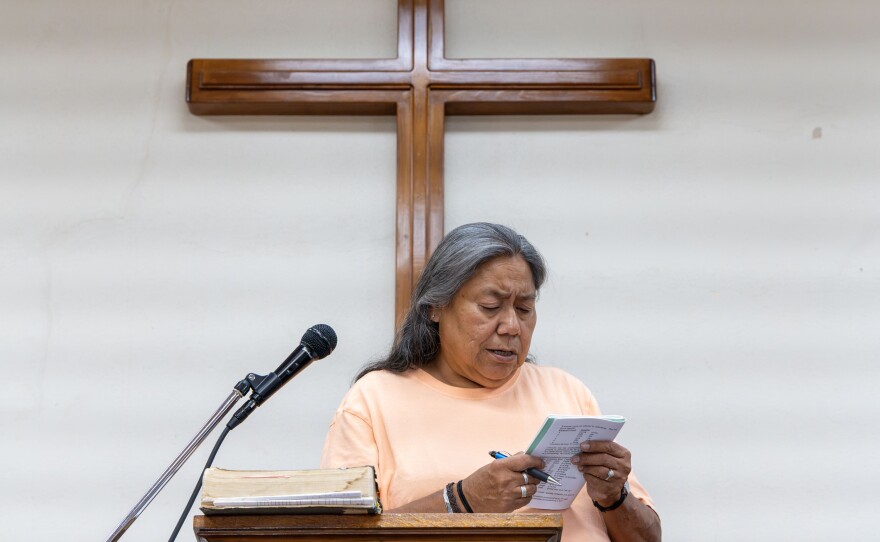

Miles of flat land in southwest Oklahoma surround a historic Comanche church called Deyo Mission. Some tribal citizens fear it could be collateral damage if the Westwin Elements demonstration plant in Lawton continues its nickel refining operations.

“This building and this land has been here a long time, dedicated to the Lord,” Kathleen Tahah, the Deyo Mission lay minister, said during a Sunday service in late May. “We’re protectors of the land, of the air, of the communities that we serve. He’s placed us here to do all those things.”

The church, established in 1893 by Elton Cyrus Deyo, acted as a community hub where Comanche Baptists would ride wagons to attend services in its early days.

The Deyo Mission cemetery, also located on the church’s grounds, chronicles a more recent history of the tribe and its struggles. Some Comanche children who walked on during the smallpox epidemic are laid to rest there. At the front edge of the cemetery, past an American flag, is a view of the Westwin Elements demonstration plant.

The Deyo Mission is about only a few minutes’ drive from Westwin’s refinery, a growing Goodyear tire manufacturing plant and a paper factory. All of these structures are situated on the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation, commonly referred to as the KCA. The reservation was ruled as disestablished by an Oklahoma court, but many tribal citizens consider it intact.

“They should have had a better place to build that somewhere that wasn’t all close to people,” Tahah said. “They’re putting lives at stake with whatever that is.”

Tahah voiced uneasiness about how late she found out about Westwin Elements and its potential impacts on the church and cemetery, given its close proximity and environmental risk. Others in the community share similar frustrations.

Built-up feelings of betrayal, anxiety and outrage caused by a lack of input and transparency ultimately boiled over during a Comanche Nation Business Committee meeting on Feb. 3, 2024, after the plant’s groundbreaking celebration had already taken place.

Christina Cooper, the tribe’s environmental director, said during the meeting that she had not received prior consultation regarding the plant’s development, leaving her team in a reactive position. Martina Minthorn, the Comanche Nation’s tribal historic preservation officer, expressed similar concerns.

“We have been waiting, watching the news, knowing this is coming down the pipeline, but never getting any type of information into our office, just like the EPA office,” Minthorn said. “Once they go to full refinery, that’s going to be very close to Deyo Mission.”

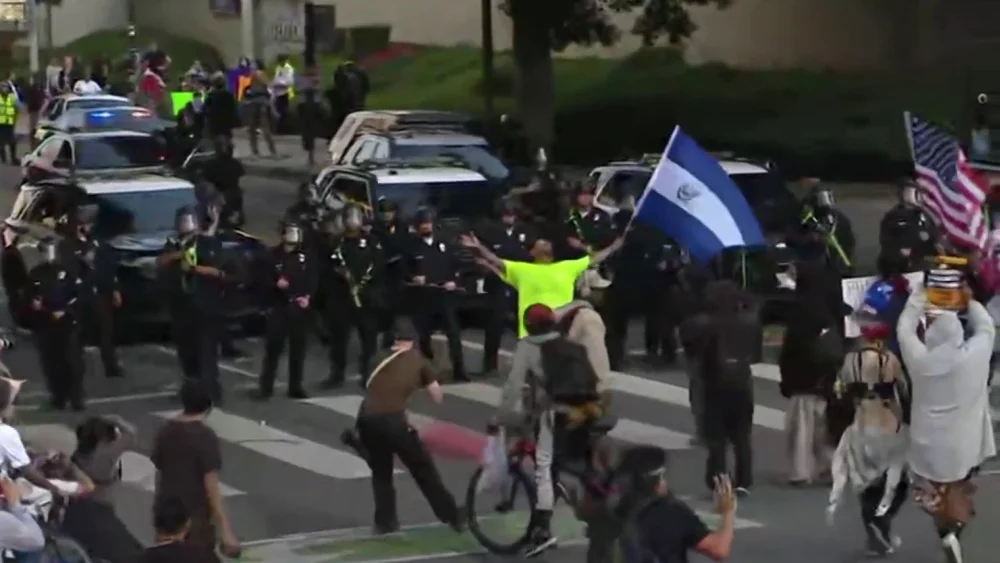

Some see the fight over Westwin as similar to the one on the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, where Indigenous protestors fought to protect tribal sovereignty and water rights from a natural gas pipeline.

“I went to Standing Rock four times,” Minthorn said. “It’s [the refinery is] going to be right here in our own backyard, so it’s sad to see that.”

Many Comanche citizens blamed then-Chairman Mark Woommavovah for not being upfront about his knowledge of Westwin Elements and his unauthorized endorsement of the plant during a City of Lawton council meeting on Aug. 16, 2023.

“Thank you for the invitation to the table,” Woommavovah said during the meeting. “I believe in Westwin Elements. … they are going to add value, not only to our community but to our state.”

As a result, he was eventually censured and replaced, and the Comanche Business Committee passed a resolution opposing the plant until an environmental assessment is conducted.

Woommavovah declined to comment on his involvement with Westwin Elements for this story.

Later in February 2024, more passionate discussions — many of which were skeptical or dismissive of the plant — broke out during an intertribal meeting of the KCA tribes and Westwin Elements officials.

KaLeigh Long, CEO of Westwin Elements, said this came as a surprise because she had met with former Comanche Chairman Woommavovah, the Comanche Gaming CEO and Kiowa Chairman Lawrence Spottedbird and had thought those conversations were positive.

“We had talked about ways that we could bring and support equity within the tribe, high-paying jobs, technical development programs,” Long said in a Westwin boardroom. “After we met, made the site selection decision …there was some voted-on opposition from the tribal community against Westwin. I was shocked to learn that, because when I had met with the leadership at that time, that’s not what I understood to be the case.”

Previous talks with tribal leadership ultimately fell flat due to rallying opposition within the KCA community. The Kiowa Tribe and the Apache Tribe of Oklahoma passed similar resolutions opposing Westwin’s plant due to its potential harm to sacred sites, community members and agricultural resources.

However, the disapproval did not change the company’s direction, as it continues to push toward its mission: to earn a win for the West.

What is Westwin Elements exactly?

Westwin Elements boasts that it is the country’s first major nickel refinery. Currently, it operates a 5,000-square-foot demonstration plant in Lawton, developing samples for potential customers and conducting research, development and training.

The company said it has more than 250 years of combined technical experience among its leadership. Although KaLeigh Long, the 30-year-old CEO, is relatively new to the industry.

“I didn’t know anything about critical minerals until I had started working with Congolese —I knew very little, I should say,” Long said.

In an interview for the podcast “This is Oklahoma,” Long described how she met a lawyer from the Congo in 2016 at a Leadership Institute conference, which aims to foster conservative leaders. Following this encounter, Long went on to study critical minerals at the Institute for World Politics from 2017 to 2019 and worked on Congolese political campaigns.

“I was very compelled to have an equitable influence in this industry and the supply chain,” Long said. “And I drew the conclusion that no amount of state department or government or NGO protest or pressure was really going to clean it — that somebody had to come to have a business influence in here to actually inspire people to do the right thing.”

Westwin Elements is not a mine, so it relies on extracted materials — most of which come from Turkey, with some also sourced from Australia, according to Long.

Initially, the company proposed refining cobalt, nickel and other ethically-sourced critical minerals, but after facing setbacks with a metal refining technology provider called CVMR, the startup pivoted to focusing on nickel.

“There is an envied global resource right now, and it’s no secret,” Long said. “And that’s critical minerals.”

The final product Westwin Elements produces in its refinery is high-purity nickel, which can be used in jet engines, missiles, rechargeable batteries and stainless steel. Nickel is considered a critical mineral by the U.S. Geological Survey, meaning it is essential for the country’s national security or economy.

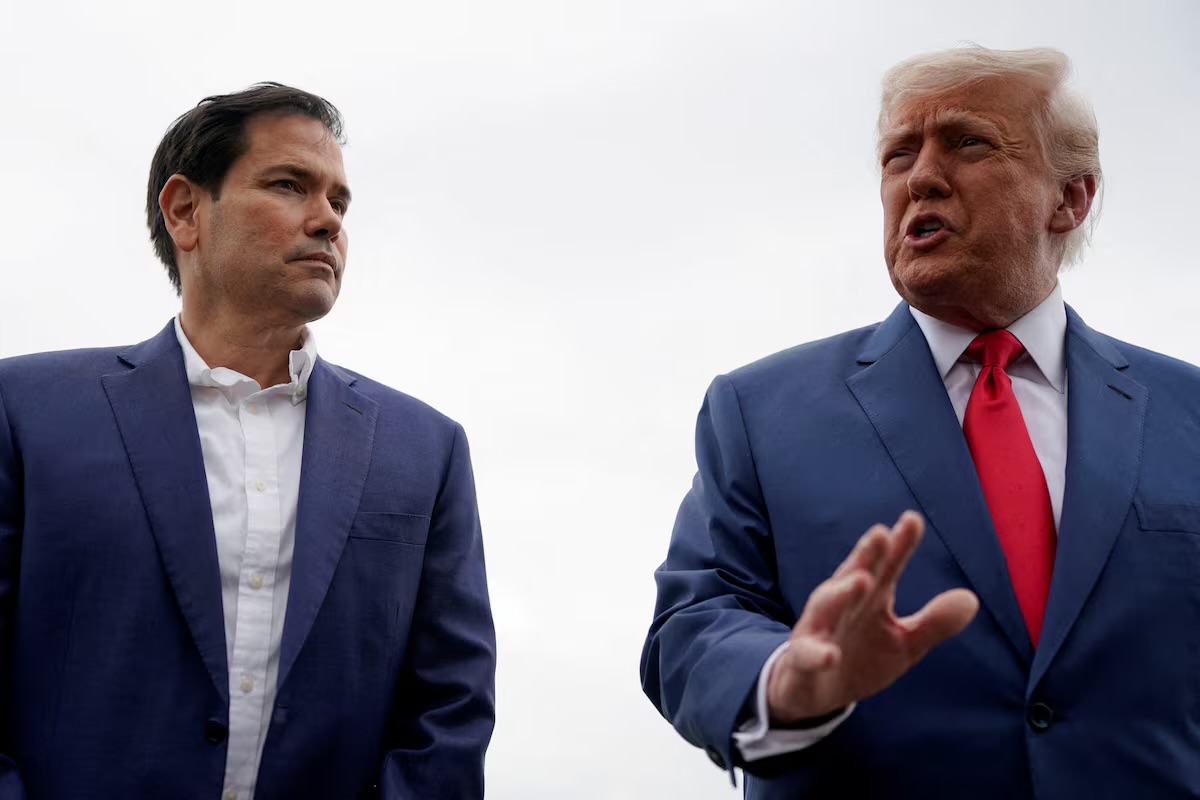

Long’s vision aligns closely with President Trump’s and has impressed Lawton officials, who offered the company incentives.

“We support rigorous environmental standards,” Long said. “But we certainly wanted a process that wasn’t bureaucratic …and what we found in the state of Oklahoma and the locality of Lawton is that it was an efficient process.”

She said Westwin Elements has raised about $77 million. Long herself was the company’s first investor.

“If this were all up to me, it probably would certainly fail,” Long said. “So I’m just going to trust God.”

What does Westwin Elements’ refining process entail?

Jeannie Bowden is Westwin Elements’ Chief Administrative Officer. She said an easy-to-understand explanation of Westwin’s refining process is that they essentially take dirt rock from the ground and remove ‘the waste’ from it to produce high-purity nickel. It achieves this through a closed-loop system, utilizing the Mond process, a century-old technique that uses carbon monoxide to extract pure nickel from an ore, creating a dangerous substance called nickel carbonyl for part of the process.

During a training with Lawton first responders in March, Westwin Elements Chief Operating Officer John Schelegey recalled a real-life anecdote about the dangers of nickel processing. He said a man named Brian was working with liquid nickel carbonyl, which becomes a toxic gas when exposed to air.

“He pulled his mask off to scratch his nose, put his mask back on, not knowing that a droplet of nickel carbonyl was on his glove,” Schelegey said during the training. “He breathed in all that nickel carbonyl, went home, got worse. …By the time he got to the hospital, it was too late.”

Schelegey said that was the biggest learning experience in his career, and he is committed to never letting that happen again.

To protect themselves, Westwin Elements plant workers wear breathing apparatuses and have carbon monoxide detectors on their clothing, according to Bowden. She also noted that the equipment is bolted into the ground, and if anything went awry, everything would shut down and be contained.

Is it safe?

“Do you trust a refinery only built to withstand F2 winds?” a billboard has asked Lawton drivers since April 2024. The message was paid for by Westwin Resistance, an Indigenous-led coalition at the forefront of pushing back against the Lawton refinery.

Kaysa Whitley, the coalition coordinator of Westwin Resistance who is Kiowa and Absentee Shawnee, consistently speaks out against Westwin Elements.

“Sometimes disruption looks like going to City Hall and getting in their faces and getting the police called on you,” she said as a speaker at Northeastern State University’s Symposium on the American Indian. “Sometimes it looks like a prayer ceremony. … Sometimes it’s a little bit funny.”

Whitley, who is also a Lawton resident, questions how the plant will be regulated by the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, given that it’s the first of its kind refinery in the state and nation.

“Our mayor used to be able to say stuff like ‘trust the process,’” Whitley said. “And so literally, like our one job has been to prove that you cannot actually trust the process.”

In March, after strong winds blew through the state, resulting in multiple wildfires, the group posted a video on Facebook showing Westwin Element’s “W” sign partially missing to the tune of ‘Oklahoma!’.

Whitley’s position is funded by Honor the Earth, a larger international Indigenous-led coalition, through its capacity support program designed to support frontline, grassroots Indigenous communities resisting fossil fuel extraction or green colonialism.

“Now here in the so-called U.S., we’re starting to see the impacts of this ‘clean transition,’ and so we’re starting to see the impacts of that in our Indigenous communities,” Krystal Two Bulls, Honor the Earth executive director, said in an in-person interview. “And we’re being targeted.”

Long has pointed mainly to Honor the Earth as the primary reason why opposition to the refinery ramped up.

However, for Whitley and Honor the Earth supporters, their public outcry is part of a larger mission to strengthen tribal sovereignty, community organizing efforts and the health and wellness of future generations who will inhabit the Earth.

“Our sovereignty is going to be the last line of defense for Mother Earth,” Two Bulls said. “And so for us, we’re saying land back and our sovereignty is the solution.”

Back at Deyo Mission church, Minister Tahah has largely stayed out of the Westwin fight and has chosen to pray rather than protest. But her worries remain.

“[I’m concerned] that we would lose the land,” Tahah said. “[That] we wouldn’t be able to come and worship out here as a church family.”

The efforts to shut down Westwin Elements continue in Lawton while questions swirl over how the startup company is able to operate despite tribal opposition.

The next story in the series, supported by the Earth Journalism Network, will explore the history of the lands now known as the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation and why Westwin Elements could begin operations even with tribal pushback.